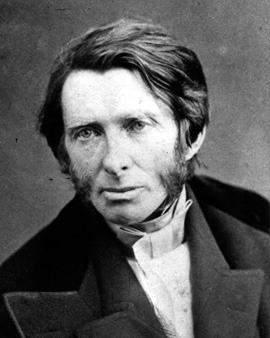

Where to begin, with this Leonardo da Vinci of the 19th century, who pursued such wide-ranging interests and left such a clear mark on the history of art?

In his memoirs, John Ruskin mentions that he taught himself to read and write while still at pre-school age. He accompanied his parents on business trips first to the British Isles, later to France, Belgium, Germany and Switzerland. He visited stately homes, gardens, galleries and other culturally interesting institutions with them. Thus the foundation for his interest in architecture, history and art was laid at an early age. The Alps and other extraordinary views of nature made an equally lasting impression on him. Rather unmotivated, he graduated from Oxford and worked for nearly 20 years on his "History of Modern Painting," which produced a close encouragement and attachment to the British painter William Turner. Ruskin was one of the most prominent members of the Arts and Crafts movement, the English counterpart to continental Art Nouveau. He defended the painting style of the Pre-Raphaelite John Everett Millais, although the latter stole his wife. In general, he was unlucky in his relationships with women. He had to settle for platonic friendships or rejected marriage proposals.

All the more enthusiastically Ruskin pursued his art historical studies. With the treatises "The Seven Lamps of Architecture" and "The Stones of Venice" he presented milestones of architectural theory. He laid the foundations for dealing with contemporary architecture as well as for theory and practice in the preservation of historical monuments. The latter were at odds with the views of the Frenchman Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, as Ruskin advocated the preservation of historical transformations in architectural monuments, while Viollet-le-Duc advocated restoring historic buildings to their original condition. Ruskin paid particular attention to the Gothic period, which was readily reinterpreted as neo-Gothic in the 19th century and found its way into architecture as well as decorative arts and painting. He held a chair of art history at Oxford, and for over half a century Ruskin was publicly concerned with nature, geology, architecture, art and literature. He considered economic aspects, contributed to the field of mythology, and discussed ethical, historical, or religious issues. His scepticism about increasing industrialization, his concerns about the loss of manual skills and last but not least his social criticism of capitalism and Marxism influenced numerous personalities, below you for example Mahatma Gandhi.

As a writer, art historian and social philosopher, his work in the field of painting and graphic art concentrated on detailed architectural views, realistic landscape impressions and selected nature studies, which reflect his wide-ranging interests. With his self-portraits, on the other hand, he seemed to have explored purely himself and his manifold interests.

×

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-208986).jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-208986).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-56825).jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-56825).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-568748).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-568748).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-568579).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-568579).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-568752).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-568752).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-72085).jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-72085).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-206645).jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-206645).jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-59455).jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-59455).jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-145035).jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-145035).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-95395).jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-95395).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-80233).jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-80233).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-160143).jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-160143).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-264859).jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-264859).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-147610).jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-147610).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-643428).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-643428).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-559281).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-559281).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-568753).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-568753).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-172324).jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-172324).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)