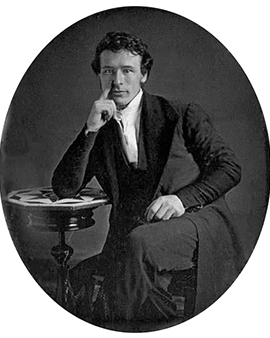

With the emergence of the technical reproducibility of reality, the question arose as to whether an image can be art. John Jabez Edwin Paisley Mayall was one of the first to answer this question in the affirmative and to develop a self-image as an artist. Mayall came to the daguerreotype from the side of the technical medium. As the son of a textile entrepreneur in the time of the Industrial Revolution, when machines began to determine production, Mayall initially occupied himself with the avant-garde natural sciences. Textiles and the technique of dyeing, led him to study chemistry and dyes. This profound scientific knowledge was of benefit to him in his work as a photographer, and his chemical education enabled him to successfully introduce several innovations in the booming daguerreotype. Among other things, he was able to limit the necessary exposure time to less than nine seconds, thus taking a significant step towards making the medium suitable for practical use. In addition, he experimented with different materials to achieve a new dimension of image sharpness.

His path from chemistry to art began with a stay in the USA. After cooperating with the American daguerreotype pioneer John Johnson, Mayall set up his own business in Philadelphia and received his first awards for his work, including from the Franklin Institute. In 1846 Mayall returned to Great Britain and met William Turner, who had broken new ground in painting with his railway pictures and speed depictions. At this time Mayall was experimenting with improving the production process of daguerreotypes in order to expand the range of common formats. Mayall claimed to be able to produce the largest daguerreotypes. Instead of a maximum format of 21.6 centimetres, Mayall worked with formats of up to 76 centimetres. He has thus repeatedly proved to be an innovator and overcomes technical limitations.

Mayall had his breakthrough at the 1851 World Fair in London. In the legendary Crystal Palace, a special exhibition of 700 daguerreotypes was dedicated to the medium of photography, including 72 by Mayall. He received an award and was celebrated above all for his technical innovations. This gave him the economically lucrative opportunity to create portraits of celebrities in commissioned work. In the 1860s he made several portraits for the royal family, which were published as so-called "carte de visit". These were images the size of a business card and became collectible pictures in public. A card of Prince Albert sold about 70,000 copies in one week after his death. With a turnover of 500,000 trading cards a year, Mayall finally managed to generate an annual income of 12,000 pounds. This enabled him to finally secure the freedom for his technical and artistic work on the medium. With his "carte de visit" and coloured daguerreotypes, Mayall conquered mass markets for photography and established a new form of perception and seeing.

×

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 (engraving) - (MeisterDrucke-37105).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 (engraving) - (MeisterDrucke-37105).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-116294).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-116294).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawin_-_(MeisterDrucke-70451).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawin_-_(MeisterDrucke-70451).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-85016).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-85016).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Dr_-_(MeisterDrucke-70504).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Dr_-_(MeisterDrucke-70504).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-88651).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-88651).jpg)

_Prince_Consort_of_Great_Britain_and_Ireland_engraved_-_(MeisterDrucke-270757).jpg)

_Prince_Consort_of_Great_Britain_and_Ireland_engraved_-_(MeisterDrucke-270757).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Dra_-_(MeisterDrucke-104017).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Dra_-_(MeisterDrucke-104017).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawing-Ro_-_(MeisterDrucke-36165).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawing-Ro_-_(MeisterDrucke-36165).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawi_-_(MeisterDrucke-66534).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawi_-_(MeisterDrucke-66534).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Dr_-_(MeisterDrucke-43493).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Dr_-_(MeisterDrucke-43493).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawin_-_(MeisterDrucke-87535).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawin_-_(MeisterDrucke-87535).jpg)

_Princess_Royal_of_Englan_-_(MeisterDrucke-274916).jpg)

_Princess_Royal_of_Englan_-_(MeisterDrucke-274916).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound - (MeisterDrucke-266176).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound - (MeisterDrucke-266176).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawing-_-_(MeisterDrucke-64943).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawing-_-_(MeisterDrucke-64943).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_-_(MeisterDrucke-86871).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_-_(MeisterDrucke-86871).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound after a photograph - (MeisterDrucke-158843).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound after a photograph - (MeisterDrucke-158843).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawi_-_(MeisterDrucke-116360).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawi_-_(MeisterDrucke-116360).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_Th_-_(MeisterDrucke-74585).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_Th_-_(MeisterDrucke-74585).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Dra_-_(MeisterDrucke-94779).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Dra_-_(MeisterDrucke-94779).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 (see 266637 for detail) - (MeisterDrucke-83634).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 (see 266637 for detail) - (MeisterDrucke-83634).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_D_-_(MeisterDrucke-68942).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_D_-_(MeisterDrucke-68942).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawing-R_-_(MeisterDrucke-36300).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawing-R_-_(MeisterDrucke-36300).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-113417).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-113417).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_-_(MeisterDrucke-99070).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_-_(MeisterDrucke-99070).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_Th_-_(MeisterDrucke-66498).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_Th_-_(MeisterDrucke-66498).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-97678).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-97678).jpg)

7th Earl of Cardigan engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-59193).jpg)

7th Earl of Cardigan engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-59193).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-107775).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-107775).jpg)

3rd Viscount Palmerston engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-90790).jpg)

3rd Viscount Palmerston engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-90790).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-69003).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-69003).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 (engraving) - (MeisterDrucke-35830).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 (engraving) - (MeisterDrucke-35830).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawi_-_(MeisterDrucke-44519).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawi_-_(MeisterDrucke-44519).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_-_(MeisterDrucke-105948).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_-_(MeisterDrucke-105948).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-103971).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-103971).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_-_(MeisterDrucke-42151).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_-_(MeisterDrucke-42151).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Draw_-_(MeisterDrucke-70570).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Draw_-_(MeisterDrucke-70570).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

engraved by GJSto - (MeisterDrucke-247970).jpg)

engraved by GJSto - (MeisterDrucke-247970).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_Th_-_(MeisterDrucke-54892).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_Th_-_(MeisterDrucke-54892).jpg)

Lord Clyde engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-87228).jpg)

Lord Clyde engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-87228).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Dr_-_(MeisterDrucke-96818).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Dr_-_(MeisterDrucke-96818).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawing-_-_(MeisterDrucke-51167).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawing-_-_(MeisterDrucke-51167).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-52638).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-52638).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_-_(MeisterDrucke-107318).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_-_(MeisterDrucke-107318).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_-_(MeisterDrucke-90822).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_-_(MeisterDrucke-90822).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

1st Baron Westbury engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-54163).jpg)

1st Baron Westbury engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-54163).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 (detail of 266636) - (MeisterDrucke-69463).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 (detail of 266636) - (MeisterDrucke-69463).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 (see 266631 for detail) - (MeisterDrucke-103308).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 (see 266631 for detail) - (MeisterDrucke-103308).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Dr_-_(MeisterDrucke-56382).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Dr_-_(MeisterDrucke-56382).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound after a photograph - (MeisterDrucke-196397).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound after a photograph - (MeisterDrucke-196397).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_Duc_de_Malakof_-_(MeisterDrucke-50567).jpg)

_Duc_de_Malakof_-_(MeisterDrucke-50567).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawing-_-_(MeisterDrucke-66261).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawing-_-_(MeisterDrucke-66261).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-109579).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-109579).jpg)

11th Lord Berners engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-75981).jpg)

11th Lord Berners engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-75981).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_-_(MeisterDrucke-56511).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_-_(MeisterDrucke-56511).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

KCB engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-114484).jpg)

KCB engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-114484).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photo - (MeisterDrucke-219476).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photo - (MeisterDrucke-219476).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-94607).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-94607).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-111405).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-111405).jpg)

KCB engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-55910).jpg)

KCB engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-55910).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-67300).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-67300).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_-_(MeisterDrucke-63517).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_-_(MeisterDrucke-63517).jpg)

1st Earl Russell engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-76801).jpg)

1st Earl Russell engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-76801).jpg)

1st Earl of Kimberley engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-59300).jpg)

1st Earl of Kimberley engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-59300).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-74535).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-74535).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawing_-_(MeisterDrucke-62582).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawing_-_(MeisterDrucke-62582).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 (engraving) - (MeisterDrucke-35764).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 (engraving) - (MeisterDrucke-35764).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_f_-_(MeisterDrucke-267023).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_f_-_(MeisterDrucke-267023).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-102974).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-102974).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Dr_-_(MeisterDrucke-80005).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Dr_-_(MeisterDrucke-80005).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 (see 266634 for detail) - (MeisterDrucke-108312).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 (see 266634 for detail) - (MeisterDrucke-108312).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Dr_-_(MeisterDrucke-105551).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Dr_-_(MeisterDrucke-105551).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-64688).jpg)

engraved by DJ Pound from a photograph from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages Volume 2 published in London 1860 - (MeisterDrucke-64688).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Draw_-_(MeisterDrucke-81802).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Draw_-_(MeisterDrucke-81802).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawing-Ro_-_(MeisterDrucke-53333).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawing-Ro_-_(MeisterDrucke-53333).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawing_-_(MeisterDrucke-111437).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_Drawing_-_(MeisterDrucke-111437).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_-_(MeisterDrucke-50650).jpg)

_engraved_by_DJ_Pound_from_a_photograph_from_The_-_(MeisterDrucke-50650).jpg)