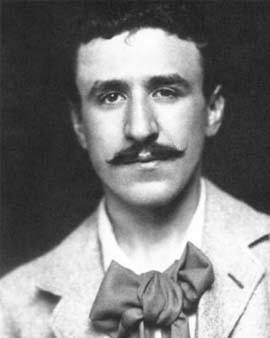

Like many artists of the Art Nouveau period, Charles Rennie Mackintosh strove for a universal design that related to architecture, interior design, and everyday objects, in other words, to virtually all of everyday life. Thus, in addition to houses, he designed a wide variety of furniture, patterned curtains, had cutlery and metal formed, sketched book covers, and dealt with a wide range of other decorative arts. In addition, he also made flower studies, ornamental and architectural sketches or landscape views.

He was formative for the architectural scene in Glasgow, influenced with his black and white style significantly the Vienna Secession and the Wiener Werkstätten as well as the German production facilities in Hellerau. Innovative and new living concepts developed there radiated into the Bauhaus and laid the foundation for modern furniture design as we know and appreciate it to this day. Mackintosh's wife Margaret MacDonald, who was herself artistically active, was always decisively involved in Mackintosh's ideas and concepts. Mackintosh, in turn, had been influenced by his father's horticultural ambitions and liked to incorporate a stylized rose or other floral elements into his work. In addition, he was influenced by the Celtic origins of Scotland as well as Japanese artwork, which resulted in a geometric design, a certain simplicity and a symbolic language of form. Particularly noteworthy is his design and implementation of the Glasgow School of Art, which to this day is considered the masterpiece of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, and this despite an incipient alcohol dependence of its architect. Here, the design of the library is particularly noteworthy. Also for the design and implementation of four salons in Glasgow, it was not without a certain irony that Mackintosh had a significant alcohol problem, since the client, as a member of the Anti-Alcohol League, pursued the enthusiastic goal of creating a meeting place for tea drinkers in drinking Scotland and the serving of alcohol in their tea rooms was definitely not intended.

It is no less understandable, but all the more tragic, that Mackintosh's famous chairs with their high backs are now considered design classics, while the artist himself was not really able to earn much money from his designs throughout his life, and even made a move with his wife from bustling London to the remoteness of the French Pyrenees in order to save on living expenses. He died virtually penniless due to diagnosed tongue cancer after a desperate return to London, where his estate was even deemed completely worthless after the death of his wife a few years later. Possibly his alcohol problem stood in his own way as far as acquiring new and lucrative commissions was concerned. For his works were highly appreciated and praised by many contemporaries and artists. Today, they are recognized worldwide, so it cannot be attributed to a lack of quality or talent if Mackintosh's professional establishment was not as successful as that of artistically far less ambitious contemporaries.

×

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_pencil_and_-_(MeisterDrucke-1092731).jpg)

_pencil_and_-_(MeisterDrucke-1092731).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-556193).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-556193).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-587172).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-587172).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-558646).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-558646).jpg)

_1891_(pencil_and_watercolor_on_pape_-_(MeisterDrucke-383645).jpg)

_1891_(pencil_and_watercolor_on_pape_-_(MeisterDrucke-383645).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-569369).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-569369).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-579166).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-579166).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_1902_-_(MeisterDrucke-410165).jpg)

_1902_-_(MeisterDrucke-410165).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-911046).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-911046).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-383625).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-383625).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-556188).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-556188).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-383629).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-383629).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-551804).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-551804).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1475682).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1475682).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-167247).jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-167247).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_c1910_(ink_on_paper)_-_(MeisterDrucke-383621).jpg)

_c1910_(ink_on_paper)_-_(MeisterDrucke-383621).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1474807).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1474807).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-572504).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-572504).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-910053).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-910053).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1470797).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1470797).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-586957).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-586957).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-639204).jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-639204).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-587171).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-587171).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-383675).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-383675).jpg)