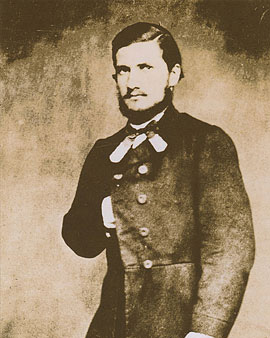

Almost unknown in Europe, Candido Lopez is one of the most popular painters of the 19th century in his native Argentina and a national icon in his time. At a time when nationalism became the dominant ideology, he gave expression to Argentine identity through his war and battle paintings. In 1863, Lopez became a soldier in the Argentine army with the rank of lieutenant. He received the officer rank for something that made him special in 1860s Argentina: he could read and write. His military service was connected with the outbreak of the Paraguayan War, which was of outstanding importance for South America. This war is still called the "Great War" in Paraguay today. It was the bloodiest military conflict that South America had seen until then. Calculated on the number of population, the war in Paraguay caused losses that are unique in world history. About 80 percent of men between the ages of 13 and 70 were killed in the conflict. Lopez found his dominant pictorial subject matter in the war. In his free time he made sketches of the fighting, which he later translated into paintings. After leaving military service, he occupied himself with the artistic design of his battle sketches until his death. His scenes of the Paraguayan War founded an Argentine national myth. After his death in 1902, Lopez was buried with military honors in the La Recoleta cemetery.

The war also had tragic consequences for Lopez himself. In the explosion of a grenade, Lopez lost his right arm, which had to be amputated from the elbow. This seemed to be the end of his artistic career at first. But with extreme discipline, Lopez managed to retrain his left arm. After seven years of training he felt himself able to continue his painting with his left arm without any restrictions.

The style of his battle scenes can be described as almost photorealistic. This was a reflex to his way into art. Lopez first trained as a daguerreotypist. This preform of photography was the first image-generating modern technology. As a photographer, Lopez acquired an excellent reputation, which earned him the commission for a portrait of the newly elected Argentine president Bartholomé Mitre in 1862. He began drawing only as an auxiliary tool for planning his photographs. It was only his encounter with the Italian painter Ignacio Manzoni that led him to consider his sketches as an independent art form. However, the planned art education in Europe fell victim to the outbreak of war. For this reason, he developed his perspective as a photographer as the basis for his artistic design. Although his paintings stand above all for the Argentine national myth, Lopez avoided underscoring his war scenes with national pathos. Instead, he retained the gaze of the photographer who, as a neutral chronicler, documents the violence.

×

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1422924).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1422924).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)